Grace VanderWaal was 12 years old when America’s Got Talent judge Simon Cowell called her “the next Taylor Swift.” “You are a living, beautiful, walking miracle,” Howie Mandel added, promising the preteen that people everywhere would know her name. Almost nine years later, they do, but VanderWaal is hardly the same ukelele-clad girl who the reality competition show’s viewers fell in love with back in 2016. At nearly 21 now (her birthday is in January), she’s no longer a child prodigy. VanderWaal is all grown up and finally ready to reintroduce herself—the real her, not the person Hollywood slowly and meticulously trained her to be.

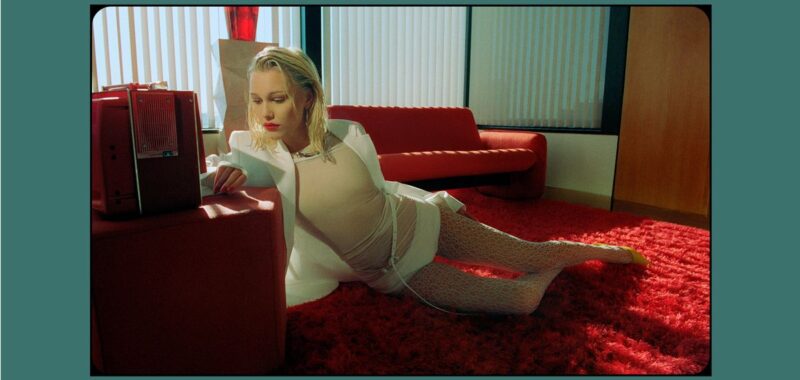

I sat down with the musician and actress in early December a little over a week after her Who What Wear shoot, where she played the part of a Wall Street exec turned ’80s film vixen. She wore a floor-length leather trench coat by Khaite styled with elbow-length gloves as well as a shirt-and-tie look that played fast and loose with real-life office dress codes. By that I mean pants were optional. “In the leather jacket, I totally felt like a dominatrix,” she tells me. “I couldn’t stop snapping my leather gloves at everyone.”

When VanderWaal logs into our Zoom call, however, she’s no longer in character. She’s curled up on a sofa inside her Brooklyn apartment with her cat Yen sitting on her lap. She is open and vulnerable, much like her forthcoming album. She has thoughts on many things, and fortunately for her (and her fans), she has a generational knack for transforming them into relatable lyrics worth memorizing and singing along to.

VanderWaal has been writing music since she was 11 years old. Songwriting was first and foremost a coping mechanism for the artist—a way of speaking her truth in moments when she didn’t have a voice. “I’ve always had a problem with vulnerability,” she says. “So it was really my one outlet.” Before long, it became clear that she had a real gift worth sharing with the world, so when she was 12, she auditioned for AGT, singing an original song titled “I Don’t Know My Name.” Mandel was the first of the show’s four judges to press the Golden Buzzer, changing the course of her life forever.

It’s only now that she’s able to recognize the impact that experience had on her as a person and, in turn, her go-to release. “Over the years, I started getting scared of the music,” she says. “I feel like it started becoming a vessel—a mirror [image] of everything I was experiencing.” Rather than writing for herself and allowing music to be the therapeutic asset it started as, she let other people’s opinions dictate what she put out. “I started viewing it as the public instead of my solitude,” she says. Her new album, which is set to be released next year, helped bring things back into perspective. “With this album, it’s the first time since I was a little girl that I got back to that beating heart,” she adds.

VanderWaal tells me the album, which remains unnamed for now, is unlike anything she has published to date. It’s only her second studio record in the nearly nine years since she was crowned AGT‘s season 11 winner. (Her first album, Just the Beginning, came out in 2017.) Since then, she’s put out the EP Letters Vol. 1 in 2019 and a handful of singles, usually around one every year. Her two most recent releases, “Call It What You Want” and “What’s Left of Me,” will be included on the new album and are meant to give listeners a glimpse of the shift in her sound brought about by experiencing heartbreak and, consequently, digging up a heap of baggage she’d long buried. “This is a vulnerable release for me,” VanderWaal says of the full-length project. It’s allowed her to take back some power over her music and remember why she fell in love with it in the first place.

The album started with the writing of “What’s Left of Me,” a raw and complex ballad about the aftermath of a broken relationship. “I had no direction. I had no concept. I just felt like I was writing from a real place,” she says. In the lyrics, VanderWaal tackles not knowing what parts of her, physically and emotionally, were left untouched—undamaged—by the person she loved. In facing that pain head-on, she says the floodgates opened, allowing her to access deeper trauma from various aspects of her life. Much of this introspection went into the other songs on the album. “I felt like I was slowly collecting this gunk that was crusting over and crusting over,” she says. Crafting each song was a way of scraping off that gunk one layer at a time. “When I finally did it, I was like, ‘Oh, that’s not too bad. It actually sounds pretty good,'” she recalls. “So I kind of was just like, ‘How deep can I go?'”

When I ask VanderWaal if the album is finished and if the remnants of that relationship are cleared away, she’s quick in her response. “Oh, there’s so much more,” she says. “I cannot wait to be in so much pain.” In fact, she had an unlikely source of influence throughout the writing process: “I was heavily inspired by that scene in Midsommar where they’re all crying and breathing together,” she explains. “I just want to vomit and cry and shake and have it all be a part of everything.”

Though she remained tight-lipped about the specifics of the album, VanderWaal did share one very piping cup of record-related tea. “I have an easy favorite song on the album that I’ve cried countless tears for,” she says. According to her, the track was always going to be the most important song on the album—even before she began writing it—due to the subject matter. It’s one she’s given a lot of thought to. “It was really, really important for me to touch on my experience with purity culture, being a child star, and being a girl,” she says. “It’s such a nuanced topic for me, and I wanted to bring in all of those layers you feel as a woman of almost resenting your womanhood and it being the epitome of pain and all these awful things toward you but also wanting to explore it freely and safely.” All of this was laced with questions about how society has shaped her beliefs on the subject. “What even is my sexuality without the world? Am I contributing to something painful for myself by simply being a sexual woman?” she questions. After much reflection, VanderWaal says she’s confident she did the topic justice: “I really love the song.”

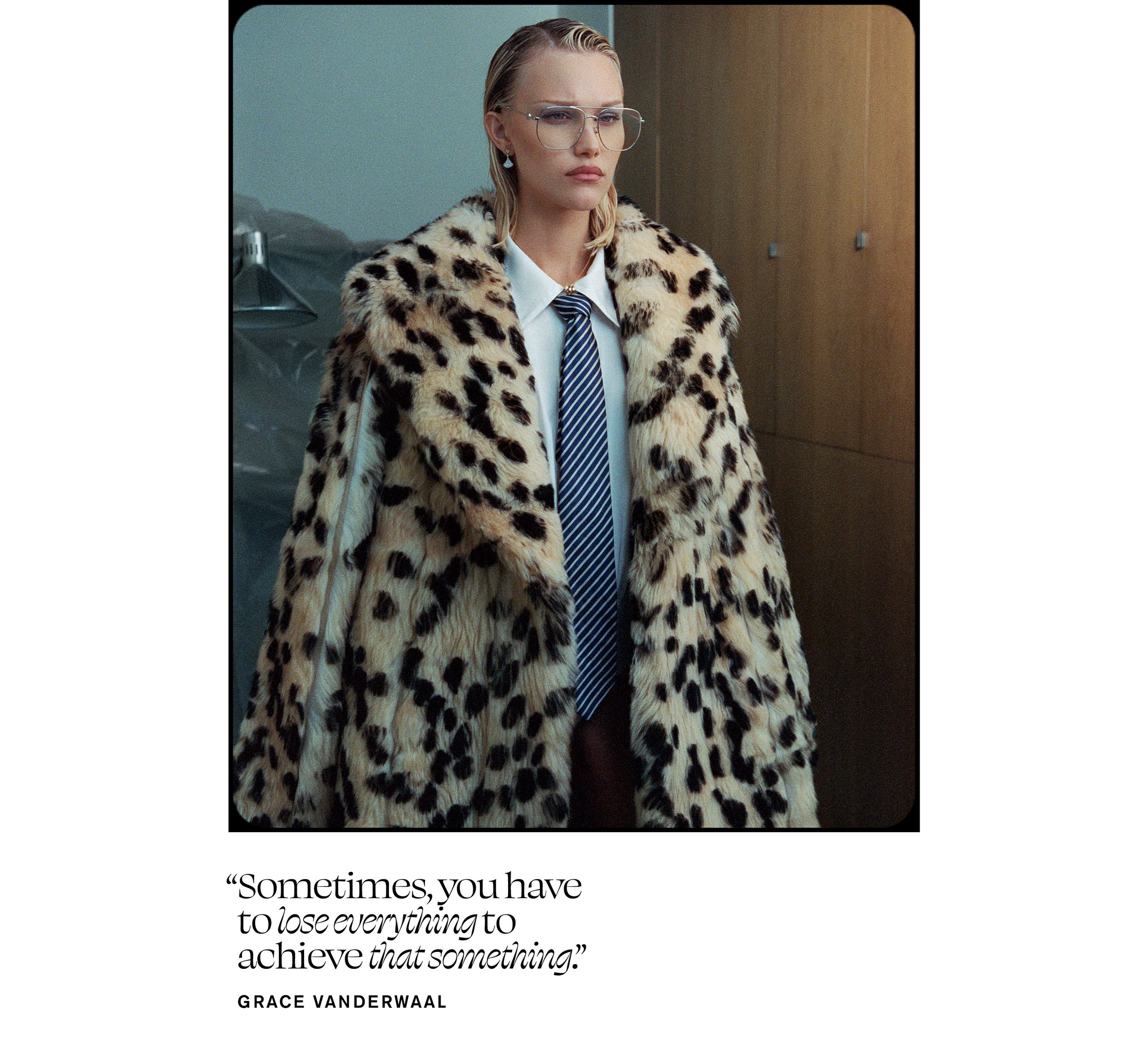

One of the main reasons why VanderWaal was able to explore topics like that one and otherwise experiment on this record was because, after spending the entirety of her early career with Columbia Records, she left the nest and signed with Pulse. (The label is known for its work with Ty Dolla $ign and James Blake.) “Sometimes, you have to lose everything to achieve that something,” she says when I ask about the switch. Columbia released the artist and, as such, still owns all of her previous discography. She had already mostly finished the album before signing with Pulse, which she says perfectly primed her to go in and pitch herself to different labels. “There was a real lack of fear in that because these were strangers at the time,” she explains. “Your validation about it doesn’t matter as much to me. If you hate it, that doesn’t mean much because I don’t even know you.” With the switch, she was finally free to ask for what she wanted and write the kind of music she’d always had inside her but was afraid to let out for fear that someone wouldn’t like it. “I think that heavily influenced the place that it got to eventually,” she adds.

The switch didn’t just affect her approach to writing. It was also a growing-up moment for the 20-year-old. When I ask her if she felt equipped to handle the business of pitching herself to new labels and closing the book on her time with Columbia, she says yes. “Very equipped. I felt like I was eager to now, as an adult, apply what I’ve learned all these years in a way that’s true to me,” she says. “It’s kind of like leaving the teacher and taking on the world for myself.”

After an hour together, I can also see how prepared VanderWaal is for the fanfare coming when her album finally drops. Twenty-twenty-four was a year for women in music. Charli XCX, Sabrina Carpenter, Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Gracie Abrams, and Ariana Grande all released monumental albums, affecting culture in every way imaginable. Given how long it has been since she released a full-length record and the fact that she claims to be a homebody, I asked VanderWaal how she feels about potentially following suit and reaching a similar post-release level of fame as the aforementioned artists. “That’s different,” she says. After eight years in the industry, fame is all she knows. “Honestly, I think that’s probably why I’m such a homebody, because you really don’t want to leave your house,” she continues. “When I do leave my house, I’m usually leaving for weeks at a time.”

This type of chaos is where the artist thrives, even if it means sacrificing the comforts and security of home. “I kind of take my reality for what it is. I’m not going to think about what I wish was happening because this is happening right now,” she says. “I do end up missing my cat, though.”

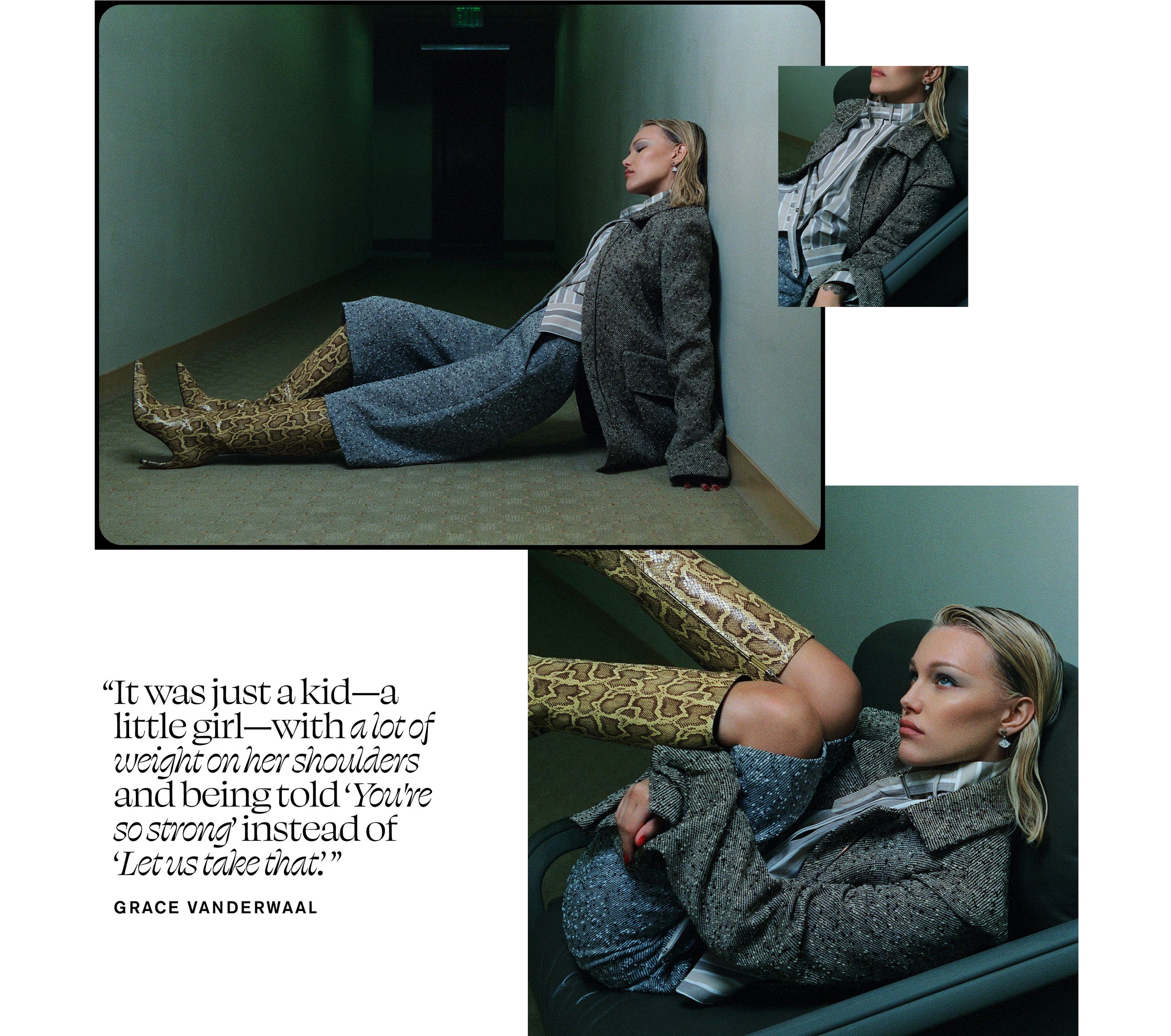

Though they’ll have to see, or rather hear, her at her absolute lowest, the idea of the public getting to know her better no longer scares VanderWaal. It’s quite the opposite. She’s ready for people—whether they’ve been fans of hers since her AGT days, discovered her elsewhere along her journey, or are brand-new to her music—to meet the real her. “It’s a very secretive, personal side of someone that’s jarring to see,” she says of what’s on the record. “That’s normally something that you might not even see in a partner for a year or two—someone baring their soul.” At the same time, the album’s narrative is relatable, even if details having to do with her childhood in the spotlight might not be. “It was just a kid—a little girl—with a lot of weight on her shoulders and being told ‘You’re so strong’ instead of ‘Let us take that.'”

Entering adulthood, VanderWaal finally felt ready to unlearn a practice that had held her back socially, professionally, and personally for most of her career: saying exactly what people want to hear. Rather than figuring out who she was and what she wanted for her life and career in her formative years, she took on a role of satisfying the desires of others, whether that meant writing music that primarily appealed to the public and record executives as opposed to herself or simply communicating with the sole purpose of having others leave conversations enamored. “When you’re in a situation like that, everything was networking,” she says. “So while I was developing my social skills, that’s how I was learning to talk to people. How can I walk away from this person with them loving me as much as possible and wanting to invest in me as a brand at 12?” She’s quick to explain that no one necessarily taught her to be this way or created some sort of character mold for her to fill. “It’s not like an Old Hollywood Judy Garland story,” she says. “It was positive reinforcement.”

Because of this, when she was upset or exhausted, she’d put up a front, masking her pain for the sake of others and never showing anyone how she felt. “I had to unlearn that. … When I got into young adulthood, I was really socially awkward, and I couldn’t make friends or connect with anybody because I only viewed talking to people as an exchange [or way of] getting ahead,” she says. “It stopped people from meeting the real me, and that is, in return, extremely lonely.” VanderWaal recalls a time when she encountered a fan and didn’t put on a performance for them like they were expecting. “I was just normal,” she says. “And I could see her face fall and be like, ‘I was not expecting you to be like this.'” Rather than further pushing her into the caricature she’d previously drawn up for herself, the interaction was a wake-up call. “I was tanking relationships, but then I actually ended up making real friendships from that,” she says. “Now, friendships are built off of me when I’m off and chill and authentic.”

I start to gather that authenticity is ultimately the through line of this time of VanderWaal’s life and career. It’s how she’s approaching music, refusing to publish her album until it’s in its absolute realest form. “I would rather not release it at all than half get the vision,” she says. It’s how she’s creating and building relationships, scraping off the gunk built up after years of putting on a front for the world. With one look at her social media feeds, you’ll discover not only an apparent lack of filters and big productions but also a clear sense that she understands her style, as she’s wearing mostly vintage and couture instead of the most recent trends by fashion‘s most recognizable designers. For example, she wore a custom corset look by model and rising star designer Liam Mackenzie to the Megalopolis premiere that Elza Khalife styled in collaboration with Janelle Best, the founder of Brooklyn-based vintage showroom Desert Stars Vintage. “I’ve always loved wearing my expression,” she says. Wearing what feels authentically her is the only way forward for VanderWaal. “It’s like a need for me,” she adds.

Because of all this, now is the perfect opportunity for the singer-songwriter to introduce the real her to the public for the first time. For once, she’s not worried about streams, album reviews, and the ways that some listeners will inevitably misunderstand pieces of the record. “I’ve made peace with that,” she says. Never again will she base her worth and how she portrays herself on the opinions of others. “I never want to sacrifice myself,” she says. “I’m sorry, but I gotta put me first.”

Talent: Grace VanderWaal

Photographer: Erica Snyder

Stylist : SK Tang

Hairstylist: Lisa-Marie Powell

Makeup Artist: Blake Armstrong

Manicurist: Jolene Brodeur

Set Designer: Cecilio Ramirez

Director, Video: Samuel Schultz

DP: Kyle Hartman

Producer: Luciana De La Fe

Associate Producer: Kellie Scott

Video Editor: Collin Hughart

Creative Director: Sarah Chiarot

Editorial Director: Lauren Eggertsen

Executive Director, Entertainment: Jessica Baker

Designer: Allyson Quirk

Copy Editor: Jaree Campbell