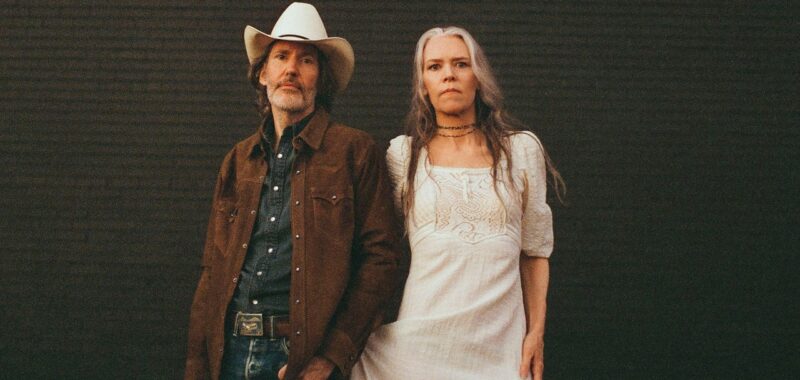

I mean, there’s a point in my life where I felt like I could probably sing any Bob Dylan song from beginning to end. If I needed to sing “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” right now, we can start on it and I probably won’t miss anything.

So I started there and then I went deep into the guitar thing. And then from a writing standpoint, a lyric-writing standpoint, I really [got] into working when we hit town and started co-writing for the first record.

The thing I’m always proudest about is, if Gil does start something, I just got to think about exactly what she’s trying to say and how to amplify it, but how to get lines in there without changing what it is, or only changing it for the better. How to focus it. You take a song like “Revelator,” which she had started out in this one place, [with] the first four lines or something, and it was so powerful, but then we’re like, Where does this go? How do we make this into something that sustains? Because I feel like a lot,

Finishing that song, I think I wrote the last couple of verses, and all of a sudden it was like, we’d been wrestling with it for months, and then they just spill out in that way. And I think it’s so amazing when you can get to the point where you feel like you’ve thought about a song so much and inhabited it enough that you can get back to that original place of inspiration and have another burst that takes you to the end of it.

Right, right, right. After leaving it alone for so long. When I go back to pieces of songs, I usually like ’em so much more than I did when I initially worked on ’em. Thank God that it’s that way. When I leave it alone, I’m like, I don’t ever want to see this piece of shit ever again. But most of the time I’ll go back and go, Oh, I had something.

Right! Like the song that became “Lawman” [from Woodland]– there was another song called “Lawman” that we wrote 15 years ago that had the same riff. I liked the riff, I liked the title. And two years ago or something, I was like, man, there was something there—if we can just find a song that will go around it. But I remember throwing our hands up with that one and then coming back, and when you come back, you can see the parts of it that you value, and you don’t care about your failure at that point. It all falls away.

Yeah. It’s like seeing a family member again. You’re like, I don’t remember that last fight we got into.

Yeah!

I always feel like I’m in a distinct place and time when I’m listening to the music that y’all make. And this is something that’s very valuable to me. That’s the thing that I love about Sticky Fingers or about Highway 61 or about Blue, about all these records that are huge, significant records. In my mind it’s because I just go to a completely different place. And I think some of that, and correct me if I’m wrong, but what I’m trying to do when I’m producing a record of my own, or sometimes it’s somebody else’s, if this is what they want, is I’ll try to make choices that could have been made 40, 50 years ago, but just weren’t. I wonder if that’s part of your approach—because if you take everything apart, those sounds could have been made a long time ago, but that particular combination of ’em wouldn’t have occurred to people.