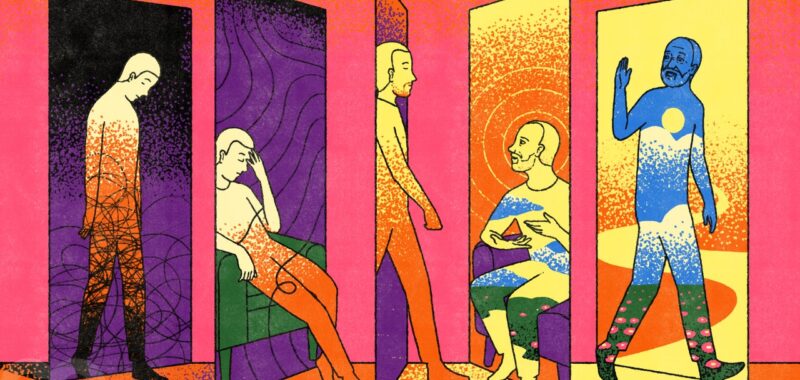

He feels less fear of the emotional reactions which he has. There is a gradual growth of trust in, and even affection for the complex, rich, varied assortment of feelings and tendencies which exist in him at the organic level. Consciousness, instead of being the watchman over a dangerous and unpredictable lot of impulses[…] becomes the comfortable inhabitant of a society of impulses and feelings and thoughts.

Suddenly I was crying in the tepid water. It sounded so beautiful, and yet so far from what I was experiencing. My inner world was still tense, unforgiving and a lot of the time, afraid. My watchman was still on the clock, dragging a baton across the prison bars inside of me.

Before this period of understanding without feeling, I had been mostly stuck in resistance, spending months arguing with Marco that I did not need or deserve the help I was paying him to give me. I vehemently insisted I had been the beneficiary of that most common of mirages, the happy, normal childhood. That this happy, normal childhood had led to a series of rigid beliefs—”I will never know what it means to be relaxed”; “I am incapable of a good night’s sleep”; “I am pretty sure I’d struggle to love a son”—was, I insisted, entirely unrelated.

Therapy is not linear. Each stage is fluid and overlaps, like tides sloshing in a rock pool. But what finally broke me free of this push and pull between denial and intellectualization was simply time—time and repetition. The boring truth about therapy is that rather than a stream of profound epiphanies, it is mostly a case of revisiting the same analysis—rising from the same undesirable thoughts and patterns of behavior—over and over again. But each time, the truth of it penetrates a fraction deeper and starts to catalyze changes in how you react to things and feel about them.

For Balick, this is the power and beauty of being in it for the long haul. “Though you keep coming back to a lot of those same repetitions, you get to them quicker, you move through them faster and you take greater risks,” he says. “Your therapist knows you and what your limits are. If it’s good, trust continues to grow, deeper things continue to be said. And it’s a real exploration—for the therapist, too.”

Today the symptoms that led me to Marco’s inbox in the first place—the drinking, the insomnia, the OCD, the unbearable daily thrum of dread—have vanished, or become so rare that when they do flare-up, I know they will pass and feel full of gratitude that they no longer dominate my life. I still have periods of crisis, of course. But the trust in myself that Rogers described has grown. My watchman only works part time. I can imagine him retiring one day—handing him a gold watch to thank him for keeping me safe all those years and then sending him, finally, on his way.

There is a six-to-18-week waiting list for therapy from the NHS, the U.K.’s national public healthcare provider. If, then, you are deemed to need what I do—psychodynamic psychotherapy, which digs into your past to help you resolve issues in your present—you might be lucky enough to get 16 sessions, or four months’ worth. When I think about where I was after that long with Marco—still completely lost, barely scratching the surface of my denials—this strikes me as a burning injustice, a sign we are still in the dark ages of treating mental health. I do not know how we get to a place where people without the means to pay for long-term private psychotherapy are able to access it through public healthcare, only that it seems a goal we should aspire to. Once, the idea of education for everyone seemed radical—now in Britain it is a basic human right.